The need to defend Australia

In 1838 four United States Navy Men-of-War sailed into Sydney Harbour overnight unannounced and unexpected. This alarmed Sydney Town greatly and alerted the Colonies to their defencelessness against invasion. The gold rushes saw massive increases in Australia’s population and wealth in the early 1850’s and it was felt amongst the Colonies that this made Australia a more attractive target for attack. The 1854 Crimean War and the “inevitable invasion” by Russia spurred the population into actively forming volunteer military groups. Upon British Forces withdrawal from Australia in 1870 the units were placed under the control of their colonial governments and were supplied with whatever weapons their government determined.

Ties to England were strong and military expeditions were sent to various overseas conflicts to aid the Mother Country. It was a significant achievement in 1900 when the South Australian warship “Protector” sailed to China to assist in quelling the Boxer Rebellion. Protector’s Engineering Officer William Clarkson was later instrumental in the foundation of the Lithgow Small Arms Factory.

The first Federal battalion of Australian soldiers sailed to South Africa in 1901 to fight in the Boer War joining the colonial troops who were already serving there. Because many of these troops arrived with different equipment to that used by the British, supply of ammunition and field repair of weapons quickly became an issue, restricting their capabilities in battle.

The South African campaign made it blatantly apparent that Australia’s isolation from its armament source could lead to serious problems in future conflicts. After federation of the states and establishment of the Commonwealth in 1901 the new Government faced responsibility for the country’s defence. The Government resolved to make Australia independent of British munitions and armament supplies. In 1907 the decision was made to establish a factory for the manufacture of small arms in Australia.

Why Lithgow?

SAF Factory from the hillside above, 1920

A number of sites had been put up as suitable locations for the new factory. In 1903 the Lithgow Progress Association and the local member of Parliament Joseph Cooke (who was later to become Prime Minister) began lobbying for the consideration of Lithgow as the site for the proposed small arms factory.

In 1904 local identity Mr William Sandford, the proprietor of the Eskbank Iron Works, added to the lobbying by proposing an extremely good offer of land, a coal supply, a rail siding and preparation of his iron works for the production of suitable steel. This offer was never taken up.

Other advantages of building the new factory at Lithgow were evident. The town was serviced by road and rail. It had a thriving iron works, coal, and limestone, and was afforded protection by its location in the western foothills of the Blue Mountains.

In 1908 land was purchased and building of the new factory commenced. When it officially opened in June 1912 the Factory had 190 employees, this grew to 373 by June 1914. The Factory floor covered approximately 90,000 square feet. The factory had its own power house, tool room and forge. Individual machines were driven by overhead pulleys with the shafting running the full length of the buildings. There were 340 machines, 11 forging hammers and 22 oil-fired furnaces.

Precision repetition manufacture

Milling section, 1912

Engineer-Commander William Clarkson wrote in a report “The object to be aimed at in establishing a small arms factory is to produce a perfect arm at the least possible cost. This can only be attained by using automatic machines, attended by human beings working with almost automatic precision. … The only skilled labour required for the manufacture of small arms is that for straightening rifle barrels. The remainder of the work is done by boys tending automatic machinery.”

In 1907 Clarkson was sent by the Australian Government to investigate arms manufacture in the United Kingdom, Europe, the United States of America, and Canada. In November 1908, resulting from Clarkson’s report and subsequent specification, tenders were called for the supply of a complete plant for the manufacture of small arms and accoutrements. The rifle to be manufactured was the Short Magazine Lee-Enfield (SMLE), the standard military weapon of British and Empire forces.

Four serious offers were received. British firms Birmingham Small Arms Co and Archdale & Co both tendered over £100,000 and 2 ½ years delivery time. British machine tool company Greenwood & Batley submitted an offer of £69,000 with 2 years delivery, and with ties to England still strong, it was assumed by most that this offer was the logical choice. The 4th tender at a similar price to Greenwood & Batley, and shorter delivery time, was from American machine tool company Pratt & Whitney at Hartford, Connecticut.

Clarkson preferred the outstanding precision and modern machines of Pratt & Whitney who were not a firearms manufacturing company, but who made machine tools capable of producing any component requiring repetitive precision manufacture. Doubts were expressed that a rifle could be manufactured to British standards by any foreign machines. After tenders closed Clarkson was sent back to Pratt & Whitney for another look, which only convinced him that his earlier impressions were correct.

The Department of Defence agreed with Clarkson, and in a highly controversial decision at the time, in some eyes close to treason, Pratt & Whitney’s tender of £68,000 was accepted for the new Lithgow factory. Pratt & Whitney offered the quicker delivery time of 1 year; much less reliance on skilled tradesmen; lower production time and costs; and training for the new factory foremen in their Connecticut factory.

It was claimed that during a demonstration at Pratt & Whitney a rifle was built in 22 hours and 36.5 minutes (the Pratt & Whitney contract stated 28 man hours per rifle). The Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield took 72 man hours and Birmingham Small Arms Factory 42 man hours.

World War I, 1914 - 1918

From a Melbourne newspaper 1918

Nobody was to expect that the world would be plunged into the conflict of World War 1 which began quite suddenly in July 1914. The fledgling factory was still not up to its full production potential of 20,000 rifles per year and only 13,800 were delivered to the Army between July 1913 and July 1914.

Upon the outbreak of war the Factory immediately set about increasing its security. The grounds were lit at night and around-the-clock armed guards were employed. The Factory had enough raw materials in store for about one year of production, and frantic efforts began to find enough raw materials and skilled men for the increase in production in the years to follow. A second shift was introduced to cope with the workload.

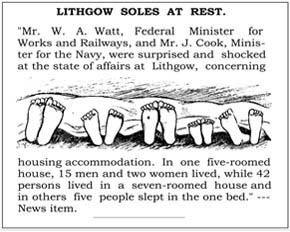

During the war employment at the factory peaked at just over 1,500 men. Lithgow at the time was unsewered, roads were dirt, and public transport was virtually non-existent. Lithgow’s long cold winters led to miserable conditions when added to the huge strain on the town’s existing services, and the critical shortage of accommodation. People were living in appalling conditions in small over-crowded and sometimes condemned houses, tents and even crude humpies. Although the situation was frequently brought up the Goverment did little to alleviate the problems. And it became worse as the war progressed.

Though not always justified, complaints about the quality of Lithgow rifles had plagued Factory Management since production began. The factory had its own quality assurance program, but after further complaints Military inspection of factory production commenced in 1916. Army Quality Assurance continued on at the Factory from that time.

Between August 1913 and July 1918 almost 100,000 Short Magazine Lee-Enfield rifles and accessories were produced at Lithgow.

Between the wars

Erecting the new Vickers building 1925

Following WWI Lithgow suffered the pain of severe decline as employment was lost from the Factory, the coal mines, steelworks and shale oil works. Calls for the Factory to take on commercial work to save jobs fell on deaf ears - the Government knew that this would create problems in other areas and placed strict conditions on allowing the Factory to seek outside work. Despite strident protests and lobbying, employment had reduced to just over 300 men by mid 1922.

Rather than close the Government factories down completely the Government ordered that they be reduced to a skeleton or ‘nucleus’ workforce to maintain capabilities and preserve skills in readiness for when they would again be needed. The factory was kept barely ticking over by building more machine tools for its sections and making and converting rifle barrels for the new Mk VII ammunition. The rest of the production consisted of a mishmash of small uncomplicated commercial work including toasting forks, washers, air brake parts for trains and other items for Government Departments including artificial limbs, aircraft parts and hand tools,

In 1930 the Government changed its position and encouraged the Factory to seek commercial work. This resulted in profitable and long-lasting work on shearing handsets, parts for cinema projectors, golf clubs, and spanners. During the economic Depression of the 1930’s the cost of producing Australian wool climbed above the world buying price. The Government ordered the Factory to copy the expensive imported shearing combs and cutters and thereby saved Australia’s most valuable export industry. The inevitable raft of complaints by the importers fell on deaf Government ears. The factory began making sophistocated SAF-LOK handcuffs in 1934 and is still making them today.

From 1923 to 1930 building extensions were carried out including a 3-story building to house the manufacture of the Vickers machine gun, a steel storage building, and the General Machine Shop - the factory’s machine maintenance area. Further extensions were erected during the 1938 - 39 period for the manufacture of the Bren light machine gun. SMLE rifle production ceased in 1929 and resumed in 1934.

World War II, 1939 - 1945

The SAF’s float in the War Loan Rally

From 1937 the Factory had been making around 30,000 SMLE rifles per year. At the outbreak of war in 1939 the demand rose to 100,000 per year, increasing again in early 1941 to 200,000 per year. On top of this was the increased demand for Bren light machine guns and Vickers machine guns, Lithgow being the only manufacturer of the Vickers outside of Britain at this time.

The factory struggled to cope with not only the increase of production for the Australian Army, but also pleas for weapons from Britain and other Commonwealth countries. Following the evacuation of Dunkirk in 1940 the British Government requested that all available Australian weapons be sent to Britain to replace losses. The Australian Government complied by sending 30,000 rifles.

Air raid precautions were completed in the second half of 1942. Factory windows were blacked out, sirens were installed and lighting rewired so that all lights could be immediately switched off, critical factory records and drawings were replicated and stored, shelter trenches were dug, and a concrete water tank installed to increase fire-fighting capacity. The penetration of Sydney harbour by Japanese midget submarines prompted the Army to build and man anti-aircraft batteries containing four 3.7-inch guns at either end of the Lithgow Valley. The factory itself mounted Lewis light machine guns atop the archway between the Toolroom buildings, later replaced by more modern Bren guns.

The Lithgow factory could not keep up with arms requirements. A new annex factory was erected at Bathurst some 40 miles west of Lithgow. This was followed by the erection of feeder factories in the surrounding towns of Orange, Forbes, Wellington, Mudgee, Cowra, Young, Dubbo, Parkes, Portland and Katoomba, which was never used. The increased demand for rifle woodwork was met by the establishment of an annex factory at Slazengers near Sydney in 1941.

By the end of 1942 employment at the Lithgow factory had grown to around 6000 with a further 6000 people employed at the various feeder factories. Once again the services of Lithgow were placed under huge strain. The perennial problem of accomodation in Lithgow meant that some families even camped in tents in the nearby pine forest without water or sanitation. Weekly production of 4000 rifles, 150 Bren guns, and 50 Vickers machine guns was achieved during this period.

As the war effort depleted the pool of available men, women were employed for the first time in large numbers. Many women were seconded from other factories. The efforts of the woman workers often exceeded expectations and earned the respect of management. It was sometimes noted that women could do a job better than men. Women barrel setters were so skilled that they earned higher than normal wages.

Post WWII period

Chidren’s Day during the 50th Anniversary celebrations, 1962

From 1945 production of the SMLE, Vickers and Bren guns ceased, and the following 2 years saw closure of all feeder factories. Workforce numbers at Lithgow had halved and the factory again entered a period of decline as it had post WW1. Once again the Factory was operating on ‘nucleus’ policy requiring that skilled workers and raw materials be kept at levels specified by the Government.

Between 1945 and 1950 military work at the factory consisted of reconditioning weapons, mainly SMLE’s and Owen guns. Refurbishment programs were also carried out on Brens, Vickers, Brownings and Thompsons, Besa cannons and Hispano cannons. Commercial production once again began to overtake military work. As part of the New South Wales Government’s re-equipping after World War II the Factory manufactured parts for locomotives (including the C38’s) and rolling stock.

Other commercial production at this time included refrigerator and Sunbeam Mixmaster parts, Westrex film projector spares, handcuffs, Slazenger golf club heads and the old turn-handle pencil sharpeners. The Factory was both retailer and wholesaler of its own Zircaloy brand open-ended, ring and adjustable spanners. Pinnock sewing machines were entering production in 1950.

Due to the Korean War military work picked up pace again during 1950. No new guns were produced but the weapons refurbishment program was increased, and urgently needed replacement parts for other military equipment were produced. Australia’s Airforce ordered refurbishment of aircraft-fitted Browning machine guns and Hispano-Suiza cannons, and manufacture of ammunition components including 20 mm shell cases, projectiles and driving bands. During 1956 the Factory manufactured parts for the 30mm Aden cannon and links for its ammnunition.

Production on the Slazenger sporting rifles, including the famous .22 began at the Factory at the end of World War II and proved a lucrative contract for about 14 years. Famous Australian sharp shooter Lionel Bibby, a Slazegers employee, contributed much to the development of the slazenger rifles.

In 1954 the Governments of Britain, Australia and Canada decided to adopt the Belgian 7.62 mm FN-FAL rifle after the introduction of the 7.62×51mm NATO cartridge. The factory began a program of modernisation and updating machinery in preparation for production of the new rifle designated the L1A1. Part of the program was to minimise costs and maximise production. In consultation with union leaders the unpopular Methods Engineering concept, including time and motion studies, was introduced. The first Factory made L1A1 self-loading rifle was proof fired in October 1958.

The bond between Lithgow and its Factory was always strong. The Factory’s 50th Anniversary was celebrated in lavish style and very much involved the town. The week-long celebration began with an inspection of the Factory by Prime Minister Bob Menzies. Among the celebrations were open day exhibitions, children’s day and a lavish ball.

[back to contents]

The Vietnam War

The team that worked on the Captain Cook Bicentennial muskets

The Australian Army had been thinking about a replacement for the Owen machine carbine since the end of the second World War. In 1957 new designs were explored, but preliminary production of a replacement did not begin until 1963. After much experimentation production of the F1 Carbine began in 1965.

With the escalation of the Vietnam War in 1964, military work again dominated factory production with the manufacture of the L1A1, F1 Carbine, and the L2A1 light support weapon. Other military production during this period included 81 mm mortar shells, parts of rocket boosters, artillery ammunition fuse parts, machettes, L1A1 grenade launcher parts, and conversion of aerial bomb arming pistols. Factory processes were upgraded and investment casting and cold barrel forging were introduced. The scant commercial work during this time included coin blanking dies for the Australian mint, door closer parts, coal picks for mechanical coal mining equipment, golf club heads and handcuffs.

Late 1967 the demand for weapons declined again and the Factory survived by manufacturing other military products, track shoes for armoured personnel carriers joining the usual military production. An order for pruning shears specially designed by the New South Wales Forestry Commission was a welcome addition to the commercial work.

A re-enactment of Captain James Cook’s landing at Botany Bay in 1770 was planned as part of Australia’s bicentennary. Period weapons were unable to be obtained and in desperation the organisers asked the Factory if 21 Brown Bess muskets and bayonets could be manufactured and ready in just one month. It was testament to the Factory’s capabilities and the skill of its workers that, working from a single sample rifle that took one precious week to arrive, the 21 muskets and bayonets were completed in time for the re-enactment. The muskets though not functional, were built to a very fine degree of accuracy, down to the proof marks on the original.

The modern SAF

At the start of the 70’s much more effort was put into safe working practices. Eye protection and compulsory hearing protection were introduced into the Factory and time lost through accidents was greatly reduced. Despite the uncertain future of the Factory as the need for its product once again diminished, installation of modern machinery continued with computerisation becoming more prevalent.

Commercial manufacturing once again expanded with new orders being taken from the mining, agricultural and transport industries. During the mid 70’s the factory was making almost 250 different types of commercial product, many required in such minor quantities that the time and pre-production development required was disproportionate to their worth. However they kept the Factory working. Customers included Lister shearing, Clyde Engineering, Borg Warner, Tubemakers, Titan Fagersta, Black Mountain Rifles, and the police force.

From 1977 the Factory began a scheme pre-training apprentices for other industries. These apprentices received a year of basic tool training and their skills were much sought after. Although it had spent most of its life trying to survive, the Factory developed a very fine reputation for the quality of its workmanship and the training of its workers.

Work continued with parts for the L1A1, APC and Leopard tank track shoes, the 66mm rocket launcher, 7.62mm barrels for L4A4 converted Brens and other ordnance components. During the 80’s the Factory was Britain’s primary source of L1A1 parts, and was exporting spares to other countries as well, however it struggled to survive without significant projects.

In 1982 the Army began the search for a new rifle and once again the Factory lived on the promise of regeneration. Preparations began for building a new rifle. The project was referred to in the Factory as SARP - Small Arms Replacement Program. After much consternation about whether the Factory would get the contract for the new rifle, finally in December 1985 it was announced that the Factory would be building the new Steyr Assault rifle and Minimi light machine gun.

The end of an era - corporatisation

Removing the Factory’s name after corporatisation

In 1988 a formal proposal was made to Government that the Office of Defence Production that controlled all Government defence entities be corporatised. This entailed reconstitution as a limited liability company, beyond the control of the Public Service, whilst remaining under Goverment ownership. The Factory became part of the Weapons and Engineering Division of Australian Defence Industries (ADI). Also in this year the first batch of 500 F88 (Austeyr) rifles was delivered to the Australian Army for testing.

Many of the people of Lithgow never really came to terms with the loss of “their” Factory. For years it had been one of the main employers and many families could claim third, sometimes even fourth, generation Factory workers. Corporatisation and the massive job losses caused persisting resentment and bitterness towards the factory that the town had once been so proud of.

ADI was sold to a private consortium owned equally by Transfield and Thompson-CSF in November 1999. Transfield’s share was bought out in October 2006. Since then it has operated as part of the Thales world-wide munitions supply group.

https://www.lithgowsafmuseum.org.au/history.html